Studies have shown that people value the products they own by how difficult they were to obtain. Things become more valuable when a sacrifice of money, time or energy was provided in exchange. This notion has given birth to hundreds of marketing techniques. This week for example we saw how the organized limited stocks in Apple’s new iPhones generated lines of thousands of fans accross the world. Even if you thought the phone was expensive, the mind somehow justifies the value and price when it sees how difficult it is for someone to actually purchase a brand new iPhone 6.

This marketing tool is used throughout many fields, including product packaging itself:

We’ve all been there… You buy a product and then spend minutes of frustration trying to open a package, using objects at hand such as nails, teeths or car keys, cutting yourselves on the plastic edge and bleeding to death while cursing out loud at the engineers and designers who came up with such a horrible packaging idea…

It turns out that because the package creates a frustration, the achievement of opening it provides a reverse satisfactory effect that continues throughout the initial usage of the product. This marketing technique is one that the French call the Oyster Effect, even though it only makes sense if you like oysters.

Well, I have now grown weary of such practices. In a world where the most valuable resource has become time, I feel like wasting time on opening a package or learning how to use a counter-intuitive product makes the product more expensive than its price tag states. In the equation, I feel like the Oyster Effect actually brings out more negative than positive.

Last week, I downloaded an app to sync up my electric car. After downloading it, I had to register the product before using it. I then had to go through an online 2-pages signup / confirmation process. I then had to set up the default settings. I then had to go through an initial tutorial. Finally I had to figure out how to sync up the car, entering lots of long alphabetic strings of random characters (think UUID) on a tiny keyboard. The whole process took me about one hour. All those steps were time-consuming. It was like trying to find the right scissors to cut through the package. Every step was enforced without any possibility to skip them, using a combination of ackward design and horrible usability before I could even have the app running. It only left me with a sour taste and a sense of frustration for the app itself. And yet I hadn’t even started using it.

One of the most challenging exercice is to ship software in a way that people can use it right away and feel right at home the second it starts.

While there are a lot of guidelines on how to achieve this, here are five that I like to follow whenever I ship a new feature or product:

Give access first. Ask for configuration later.

Noone wants to take some time configuring something they simply want to try out. Keep signup forms to a minimum. Prefer reusing accounts to storing new passwords.

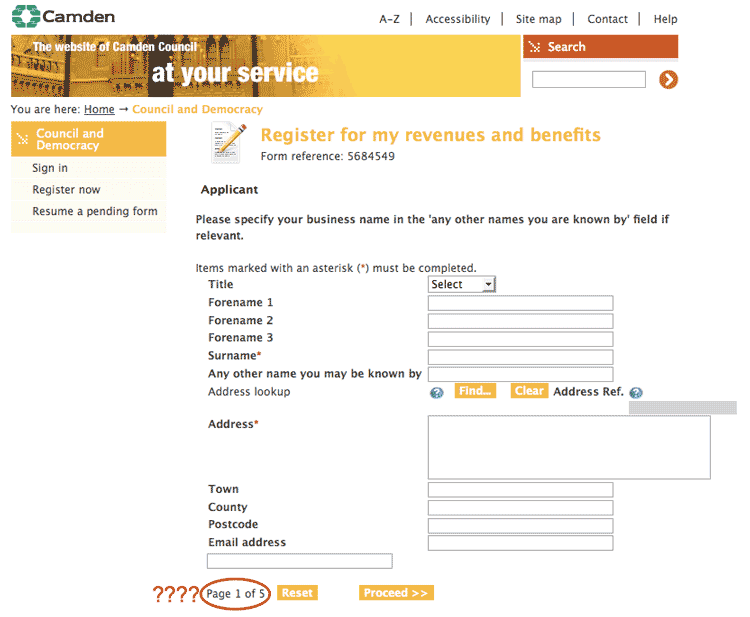

Don’t do this:

Always provide logical and non-obtrusive default options.

If you ship a programming IDE, make sure you ship it with spell checking OFF and with line numbers ON… Do not subcribe your users to anything unless they have desired to do so…

Don’t do this:

Make your software intuitive

Don’t attempt to revolutionize the standards by coming up with another icon for the Save button, or by remapping the shortcut keys that everyone is used to…

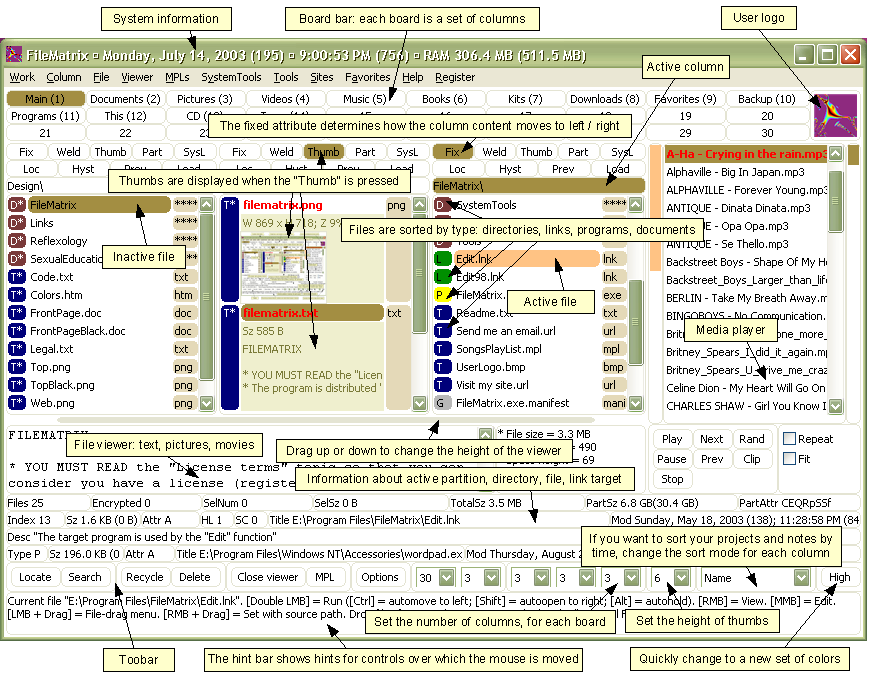

Don’t do this:

Aim for simplicity.

Limit the number of clicks required for each action. Keep the displayed information to a strict minimum.

Don’t do this:

Allow for flexibility

Provide advanced options / configuration to provide for all the other use cases you took out when refining the step before.

This week-end I played The Stanley Parable. For those who haven’t tried it, it’s an amazing experience that I don’t want to spoil. But besides providing an awesome game, the guys at Galactic Cafe provided a perfect example of simplicity, intuitivity and usability that you experience as soon as you start the game for the first time. It only takes a few seconds from the time you click Play on your OS to your first Wow.

The main reason why we create software is for our users to use them and enjoy them. The less is required of them to use the products correctly, the better the experience for both the creators and the users. As the French poet Antoine de Saint-Exupéry stated 75 years ago:

It seems that perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.