(5 minutes read)

My oldest son Noah turned 7 three months ago. If he could trade his family for a 2 hour session of playing minecraft, he would do it in a heartbeat. The other love of his life is Super Mario Maker, and it’s been a thrill to see him play the same game and levels that I played when I was his age. About 5 months ago, I left my family for my yearly pilgrimage of ludum dare: a game dev competition during which I lock myself away with friends, return to a state of primitive caveman, not sleep for 48h, and create a full game from scratch (play it at the end of this post!) As I proudly showed my revolutionary AAA title to my wife, Noah was naturally intrigued and I introduced him to the world of code, showing him how simple words (he had just learned how to read) produced an actual game. Since that very day, Noah has been asking me repeatedly to teach him how to make his own video games. And for the past 5 months, I have been looking for the holy grail of language/IDE for kids in the hope of turning that spark of interest into a memorable experience…

My quest has led me to endless forums, through which I have tried countless suggestions: SmallBasic, Pico-8, Smalltalk, Scratch, etc. I have even inquired of the Great Oracles of StackOverflow, to no avail. After 5 months, I ended up with a disappointing conclusion: nothing is even close to what I had back in another era. 30 years later, QBasic is still the best when it comes to discovering programming.

“OMG please don’t teach him GOTOs!!”

10 PRINT “OH NO, WHAT ARE YOU DOING?!!!”

20 GOTO 10Yes, QBasic is a terrible procedural language. It introduces one to concepts widely considered harmful, uses awkward syntax for implicit declarations, is not case sensitive, is non-zero-based, etc. the list goes on… When developing a skill, it is much better to acquire the right reflexes from the start rather than have to correct years of bad practice. Following this advice, I should have probably started off with the basics of the ruby language which I love. Yet, while most of those QBasic concepts are today generally considered as red flags by our peers, they each served a very specific purpose at the time: to keep the language simple and accessible, a notion that every other language has left behind in favor of flexibility, complexity and logic.

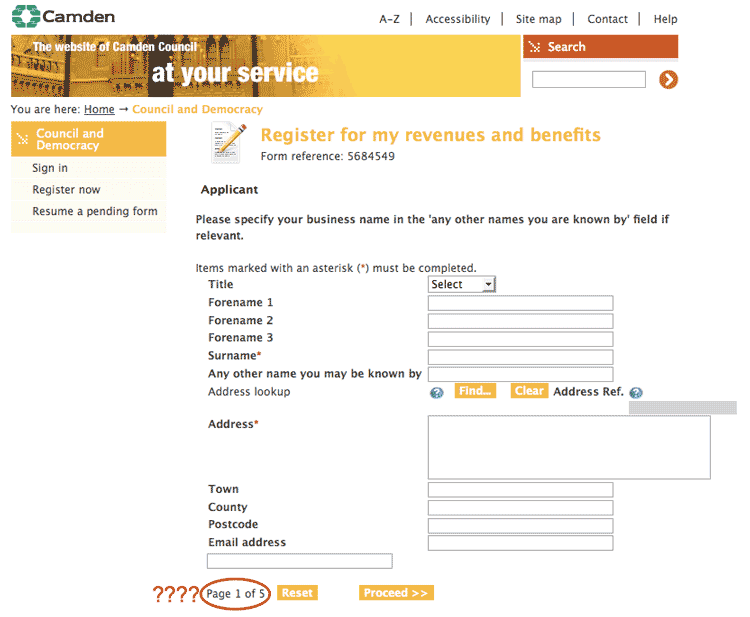

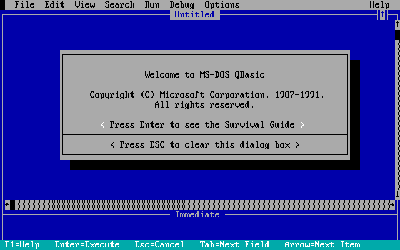

I installed QBasic on my son’s 11” HP Stream today, having to hack a DOSBox manual installation. He double clicked the icon on his desktop and in a split second, we were in the IDE, greeted with the introduction screen which brought back so many memories to my mind:

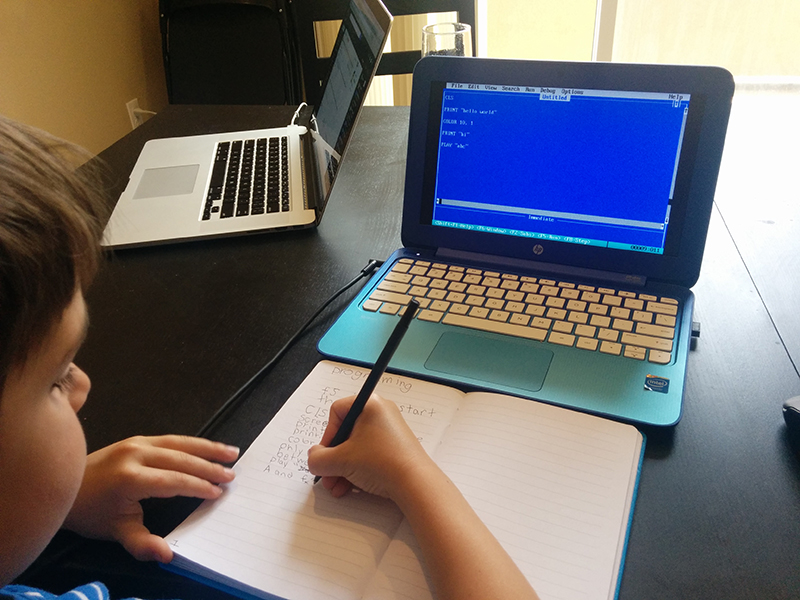

I then told Noah that there was a very sacred ritual, mandatory for anyone who enters the secret inner circle of programmers, to start off with a program that greets every other programmer out there. As I dictated the formula, he slowly searched for each key, carefully typing with his right finger the magic words: PRINT “hello world”

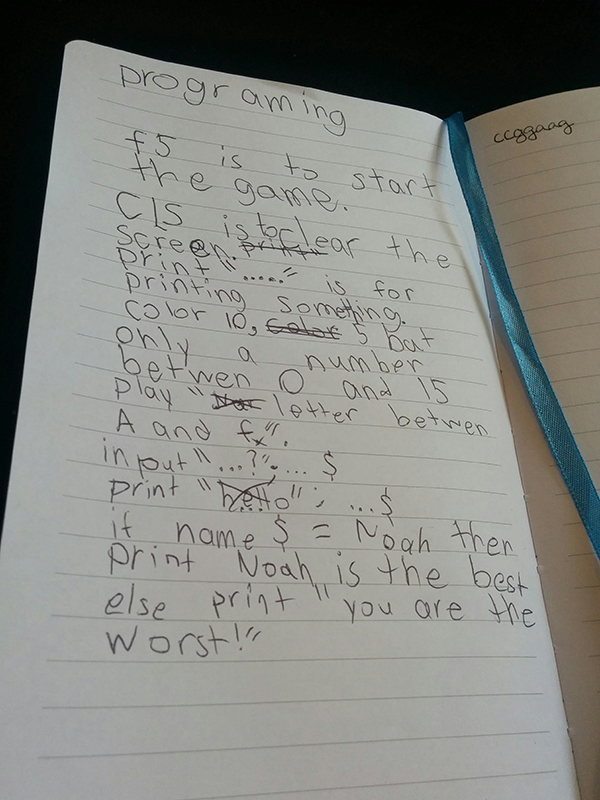

He pressed F5 and looked amazed as he saw his code being compiled into text rendered on his black screen. He smiled, gave me a high-five, and then scribbled down the code in his little notebook so that he could remember later.

We went on to a couple more commands: CLS, COLOR, PLAY, INPUT, and IF. There was nothing to explain: no complexity, no awkward operator, no abstract concepts, no documentation that needed to be read, no notion of objects/class/methods, no framework to install, no overwhelming menu/buttons in the IDE, no special keyword or parenthesis. It was code in its purest simplicity and form.

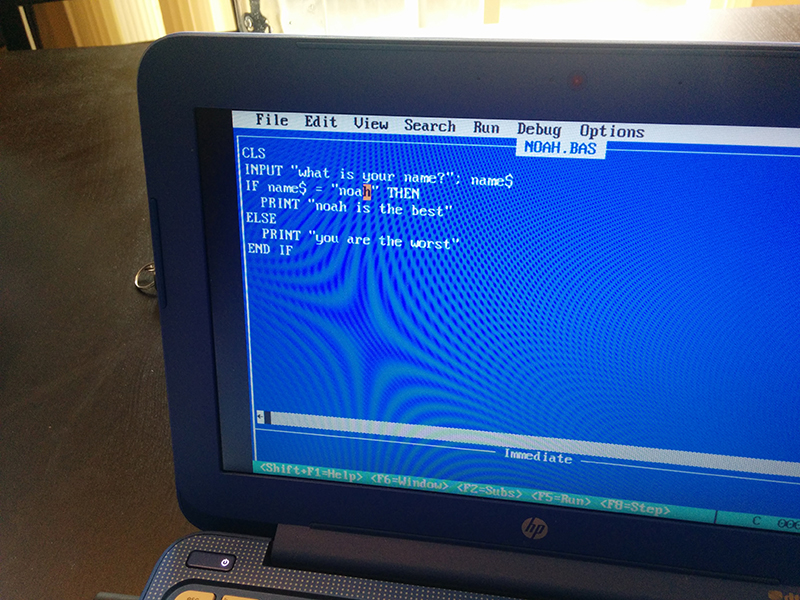

After less than an hour, he wrote his first program on his own – an interactive and incredibly subtle application which lets you know the computer’s feelings towards you as an individual and sensible human being:

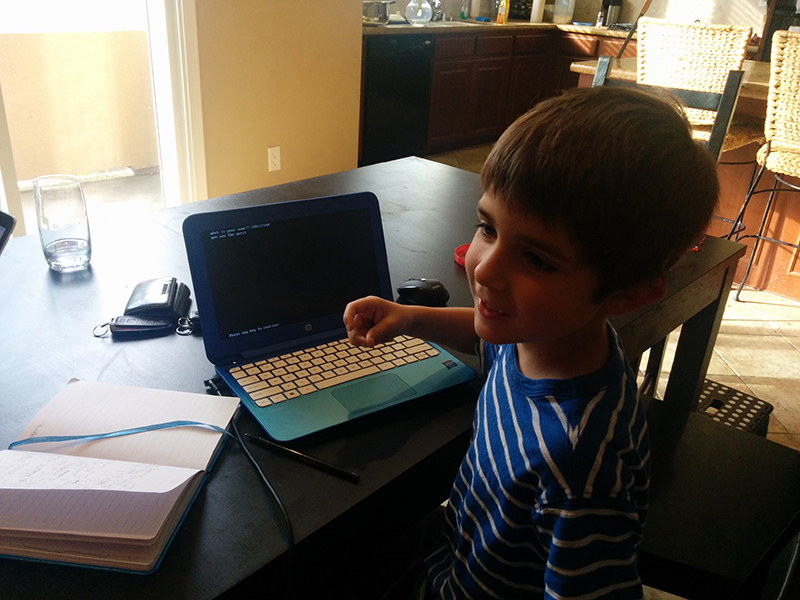

…which he ran with utmost pride for his cousin and best friend Christian:

…after which he proceeded to easily explain him how it worked and what the code was doing!

And so it was that in a single hour, my 7 year old was able to not only write his first text game, but also to experience the fun and thrill that comes from creating, compiling and executing his own little program. Bonus points, it all fit on a single notebook page:

I was so glad that he was able to understand why I keep saying that I have the best job in the world. My only regret today was to realize that in more than 30 years, we have not been able to come up with something better for our kids: Qbasic has a limited set of simple keywords (the entire help fits on a single F1 screen and is packed with simple examples!), does not distract the coder with any visual artifacts, has a very confined and cosy dev environment, shows errors as early as possible, compiles and executes the code in a heartbeat with a single key, and is extremely straightforward. We have built more robust and more complex languages/frameworks/IDEs (which are of course necessary for any real-life application), but we have never really made a simpler or more direct access to the thrill of programming than QBasic. Even running QBasic today has become dreadful to the novice that uses a modern Mac/PC/Linux machine, whereas it used to simply require inserting a 3,5” floppy in the A:\ disk drive…

Enough rant, today is all about the celebration of yet another person who discovered the excitement and beauty of programming!

Cheers!

(as promised, my AAA title for which I await EA’s call to purchase copyrights)